Improvised chalk, a wooden board instead of a blackboard, and half-broken chairs.

Drenica, 1998. Someone was trying to keep the Albanian language alive while the situation worsened due to the regime of Slobodan Milošević.

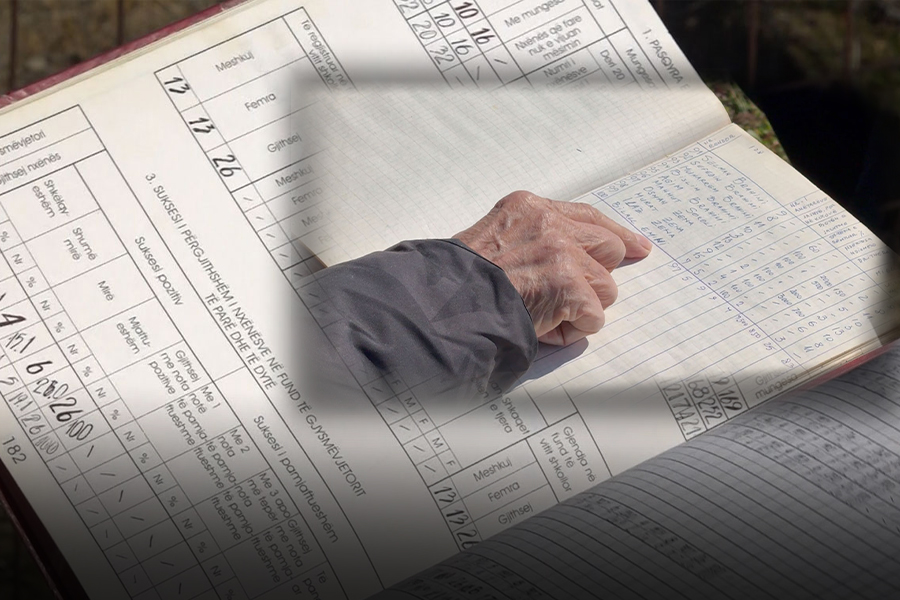

During shelling, students took shelter by ducking under school desks, and on the torn pages of half-burned notebooks, they drew pictures of destroyed houses. A testament to those days, when first-grade students learned their first letters amidst fear for their lives, is a diary from that year, preserved by former teachers.

In makeshift classrooms, with around 30 students—some sitting, others standing—teachers from the elementary school "2 Korriku" in Tice conducted lessons for about a month in two private homes since the school building was a target of Serbian army attacks.He recounts how the few remaining school desks served as shields for students and teachers when gunfire erupted.

"The classes ranged from first to eighth grade—there was no ninth grade. Each class had over 30 students because we also included children from other villages. Lessons in these two buildings lasted from May 25th until June 17th—a total of about 27 days. Each lesson lasted around 25 minutes, no more, because of the conditions. There were eight classes, so lessons had to be conducted quickly for the next group to continue. We brought in school desks, chairs, blackboards, and chalk. The students were not fully equipped with textbooks—some had them, some didn’t. Out of fear, some students might have come to school without books because after hearing shelling the day before, they didn’t know if they would return home the next day. Whenever there was heavy shelling, all the students hid under their desks in fear—not just them but even the teachers," Qorraj recalls.

Meanwhile, teacher Sokol Zeneli recalls moments when first-grade children would start crying and asking to go home to their parents after hearing the sounds of gunfire.

"When there was shelling or gunfire, they were afraid of what might happen to their families. First-grade students would say, 'Teacher, can we go home? Can we stop the lesson in case something happens to my mom or dad?' I had mixed emotions and felt terrible. We couldn’t tell the students in advance when classes would be interrupted; they only knew through their parents. The uncertainty of what would happen the next day was always there. According to my records, I had 29 students registered in my class," says Zeneli.

Teacher Sokol Zeneli, who was then teaching his second generation of students, describes the miserable conditions in which lessons were held during the war.

Meanwhile, Jahë Jusufi, the former principal of "2 Korriku" School (now named after the martyr Ismet Uka), shares a story that illustrates the hardships of that time. He recalls how one teacher ended a lesson when he heard the sound of sheep bells outside, a sound that replaced the absence of a school bell.

With whatever he could find, the veteran educator collected bits of chalk and glued them together, as even chalk was scarce in those dire conditions.

Some of the students from this school were later killed by Serbian forces during the last war in Kosovo.

/ Z. Zeneli